Seminarji in poletne šole

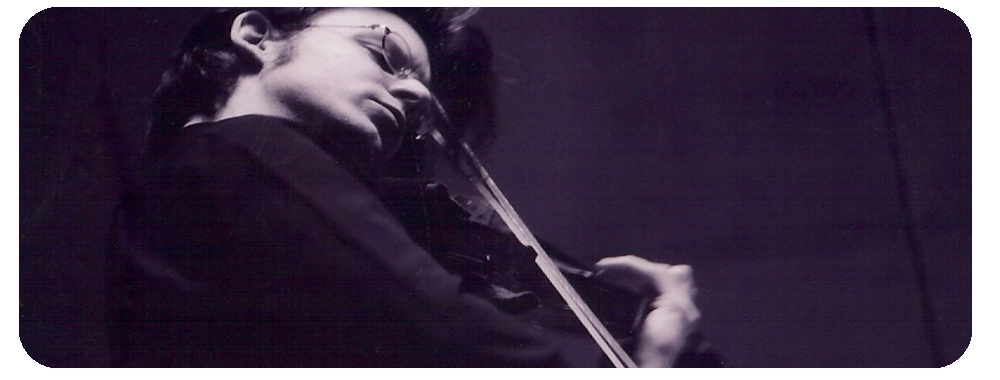

6. Poletna šola za violino v IzoliV prostorih Glasbene šole Izola bo letos potekala med 10.8.2024 (sobota) - 18.8.2024 (nedelja) 6. Poletna šola prof. Žiga Branka.

Informacije in prijava -- več >>

Latest album release

Beethoven Violin concerto

Four strokes on the timpani lead the listener into one of the most important and revered violin

concertos in the entire repertoire, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. The composition was

dedicated to violinist Franz Clement, who gave its premiere in 1806.

With the emergence of numerous virtuosi, the role of the soloist became even more emphasised in

the composition of the classical concerto. In Paris, the French violin school began to develop, whose

leading representatives, G. B. Viotti, R. Kreutzer and P. Rode, themselves wrote many virtuoso violin

concertos. In these works, the orchestra mainly served merely as an accompaniment to musical ideas

based on the violin part. The Paris violinists inspired Beethoven and influenced his style of writing for

the violin. His famous concert sonata in A major is dedicated to violinist R. Kreutzer, his last violin

sonata was premiered by P. Rode, and the influence of G. B. Viotti can be traced in the Romances for

Violin and Orchestra.

Along with the Violin Concerto, the two Romances for Violin and Orchestra, in G major and F major,

are among Beethoven’s most distinctive works for violin and orchestra. Although published as

independent compositions, they could easily have served as slow movements in the larger concerto

form. In a calm dialogue, the dominant violin shares elegant, subtle melodic material with the

orchestra.

Despite the prevailing tradition of solo works and the romantic virtuoso development of the violin

concerto, the main musical ideas appear mainly in the orchestra in Beethoven’s Violin Concerto,

while the violin part merely accompanies these ideas, colouring, embellishing and completing them

in the sense of improvisation. The content of the overall picture is based on the orchestra, and the

work is essentially a large concerto for orchestra with the addition of a violin. As well as numerous

additions and corrections by the composer, the manuscript also contains alternatives for the violin

part that could be understood as notated improvisations. The Violin Concerto did not meet with a

great deal of enthusiasm at its premiere, but it has certainly withstood the test of time. With its

undoubted compositional and substantive quality, it has gained a reputation as one of the greatest

violin concertos of all time. A concerto of timeless, deep, gently romanticised poetics, it opens with

springtime rapture and fresh energy, which later in the work experiences its autumn and

recollection. For both the listener and the performer, this is a musical story of the four seasons of

life.

DEBUSSY | RAVEL | FAURE

Musical miniatures live in their own world of mood; they are songs without words that can express a long thought in a short time. Just as words are merely a medium through which great poets convey more than the words themselves the essence of meaning and expression, music is also such a medium. The fin de siècle period in musical literature represents groundbreaking innovations that opened up new worlds of musical expression. The subtlety of Gabriel Faurè’s harmonic world, new perceptions in understanding the tonal world of Claude Debussy, and the diverse influences and experimentation of Maurice Ravel marked a new era, and the oft-quoted idea that “Where words leave off, music begins” (H. Heine) perhaps gained an even deeper meaning half a century later. This album is essentially a tribute and admiration for the great “translators” of the unspeakable and indescribable into the language of music, featuring a selection of compositions by three French masters. Ravel’s famous Pavane pour une infante défunte serves as a prelude to the heart of the impressionistic album. In choosing the works, we wanted to include two of the most important sonatas from the violin and piano repertoire (Debussy's Sonata, Ravel's Sonata), which would be accompanied by shorter, no less masterful, and most charming pieces. They have stood the test of time (Faurè’s Berceuse) and expressed mutual respect (Ravel’s tribute Berceuse sur le nom de Gabriel Faurè). We did not hesitate to include some pieces that were originally written for different ensembles and used adaptations for violin and piano (Claire de lune, The Girl with the Flaxen Hair). In an era in which artificial intelligence attempts to answer the unanswered, let us admire precisely this – the unspeakable, the indescribable (Après un rêve).

Youtube channel

L. van Beethoven: Sonata no. 5 "Spring"

During crisis of corona virus and selfisolation, recorded on digital piano (Roland FP7) and violin

Featured audio recording

E. Ysaye: Solosonata op. 27, no. 6

Sonata no. 6, which is perhaps the most challenging technically, is dedicated to the noted Spanish violinist Emanuel Quiroga, whose violin playing reminded many of his contemporaries, including Ysaÿe, of that of Pablo de Sarasate. According to certain records, Ysaÿe adapted the violinist-technical and expressive elements in this sonata to the artist to whom it is dedicated more than he did in the other sonatas. However, the sonata was never publicly performed by Quiroga. The one-movement sonata completes the large cycle of masterpieces, which open up new paths and dimensions for the violin.